Like the markets for art and luxury goods, the world of spirits is no stranger to fake and counterfeit bottles. Whisky is one of the categories most targeted, attracting the attention of numerous forgers.

Telling genuine products from fakes

Counterfeit bottles primarily affect the extreme ends of the category:

1 - The cheapest and most popular products, which generate high volumes of sales. In this case, the brands targeted are most often very low-cost blended scotches or bourbons and other entry-level Tennessee whiskeys for emerging markets. Fakes are most often produced from adulterated alcohol and in addition to the damage caused to the brand image pose a genuine health risk.

2 – The most expensive products, single malts in particular, from famous distilleries and all eras. Bottles from distilleries closed before the Second World War, whose histories are especially difficult to trace, are other common victims of fraud. In this case, the aim is not to target a market but instead the collector community, and it is this category that we will look at here

The life of a counterfeit bottle

Fake collectible bottles come from various sources, some even linked to the whisky industry itself. Up until the early 2000s, it was not uncommon for a producer to offer their distributors fake bottles, some almost truer than life, so that they could create window displays to attract passing trade and promote a particular product or range. The first edition of The Macallan Fine & Rare is an excellent case in point. The bottles could only be distinguished by a sticker on the bottom of the bottle or a missing or slightly torn back label that carried no mention of the bottle number. Although very well-informed collectors were able to tell the difference, others could not.

Macallan Fine & Rare Range

The internet and second-hand sales sites are often also rife with fraudulent practices. What’s the point in selling an empty bottle with its stopper and capsule intact for several hundred or thousand euros? This practice is in no way new, only the method has changed.

It was notably behind the first fake whisky scandal at the turn of the 21st century. A dozen distilleries saw outstanding bottles bearing their name, dating from the end and start of the 20th century, reappear as if by magic 100 years later.

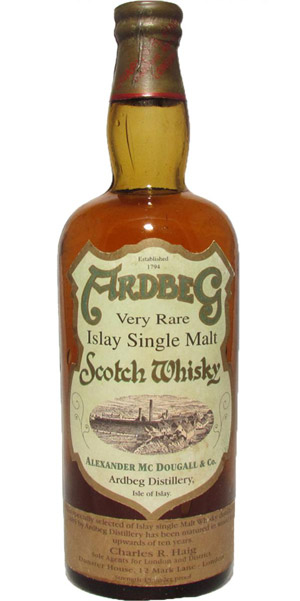

Ardbeg 1885, too good to be true

Ardbeg, Bowmore, Macallan, Lagavulin, Longrow and Talisker were the worst hit. It was also a cruel disappointment for The Macallan. Like many collectors at the time, the distillery bought many of these bottles and then used them to develop the Replica range. Four replicas were released on the market, 1881, 1876, 1874 and 1861, all based on bottles thought be original in form and content.

Fake Macallan set bought by the distillery

Although the bottles were authentic, however, their contents were not. When later carbon-dated, the majority of these bottles, which came from a range of different distilleries, turned out to have been distilled after 1955.

These fake bottles most often pass through a number of hands before reaching consumers. They will be slipped into a collection of several dozen or even several hundred or thousand bottles, and, when the collection is put up for sale, find their way onto the market. But they can also appear in isolated batches passed on through inheritance. In reality the seller is rarely aware of the nature of the bottle they are offering. And, when faced with the possibility that they may have been duped, most opt for denial.

If the transaction takes place between private individuals (who normally know each other), though delicate, the subject is generally discussed. All collectors who started their collection in the 80s-90s will, regardless of their background, have come across or heard of a fake at some point or other. And, when an entire collection is bought, it should be assumed that at least one or several of the bottles are fake

If the transaction goes through an auction house, whether online or not, it is up to the sales manager to address the issue and separate the bottles in question. When carbon-dating is not possible, the general rule is, “If it’s too good to be true, it’s because it’s fake.” Sometimes, however, even auction houses are fooled and only learn that a bottle is fake after putting it online - and in some cases never do. And so the bottle continues its journey.

Recognizing a genuine product

This requires carrying out due diligence and collecting as many clues as possible before crying wolf, because, once you start, it can be tempting to see fakes everywhere.

The historical facts

In general, anything bottled before 1950 should be treated with caution, no matter where it comes from, whether it’s from Scotland, Ireland or the United States. For the time-being, Japan has been spared from this rule due to the later arrival on the European market (in the 90s) of the first 100% “made in Japan” single malts.

The 1950s marked a turning point for the whisky industry, which had survived several major economic, political and social crises since the 1890s. First came the Pattison brothers overproduction crisis at the end of the 19th century that almost brought the Scotch whisky industry to its knees. Then came WWI and WWII, each bringing their share of destruction, pillage, distillery closures and requisitioning of sites and production equipment to support the war effort. The period in between the two wars also saw the introduction of laws and taxes often seen as punitive. When Prohibition was imposed in the United States from January 1920 to December 1933, it led to the disappearance of almost all whiskey stocks and the closure of the main market for Scotch and Irish whiskies. Finally, the crisis of 1929 that hit Ireland and Scotland shortly after led to an increase in the streamlining and closure of sites.

These events are all part of the historical background that needs to be taken into account when investigating the authenticity of bottles and the possibility of their existence. It is also important to consider the successive reigns of the kings and queens of England who all, without exception, granted their royal seal to their favour independent bottlers and distilleries, which can today be used to date a whisky.

The scientific facts and their limitations

Carbon dating is frequently used to authenticate a whisky’s distillation period. Whiskies can be dated by analysing the alcohol produced using grains harvested before or after 1955-60. This, for example, led to the unmasking of Talisker 1863, when it was revealed that the whisky it contained came from a distillation of grains harvested after 1955. The Berry Bros & Rudd Laphroaig 1903 is another great example of fraud and other bottlings in this range are also highly contested, including Highland Park 1902.

Highland Park 1902, Berry Bros and Rudd whose authenticity is still disputed today.

In contrast, other bottles passed the test rather well, such as Tobermory 1880 and Lagavulin 1920, although it remains impossible to know the exact year of distillation.

The material facts (a non-exhaustive list)

Bottles can also be dated by taking technological developments into consideration :

- by looking, for example, at their shape, the positioning of the neck and shoulders, or even irregularities and imperfections, particularly those found on the base of the bottle. Bottle markings are another incredible source of information, offering manufacturer logos, bottle codes and occasionally, for Irish whiskeys, the year the glass was produced. For example, two bottles of Power’s Gold Label, one from “1977” and the other from “1970”, bearing in mind the production site moved from Dublin to cork in 1975-76.

- The type of stopper used, whether a cork, metal or plastic screw top, or spring cap is also relevant. Consider also markings found on capsules, the material used and, most importantly, their length. Take the Laphroaig 30 Year Old “Long Cap” or “Short Cap”, for example. The first dates from the late 1990s and the second from the mid-2000s.

- The cardboard or wooden box used for transport is often marked with a rotation/inventory number (the year in which the box was filled and sealed).

- The use of transparent, green or dark brown glass.

- The way in which labels are attached, eg. traces of adhesives specific to Macallans bottled in the 1960s.

- The presence of white specks (mineral deposits that have crystallized over time) in the bottom of the bottle. Their presence in an old bottling is a reassuring sign.

Labels and laws (a non-exhaustive list)

Changes in national and European laws and regulations can also help date a bottle. Symbols, stickers, tax strips and other certificates of origin regularly change depending on the import market and era. Although the European community has begun to harmonize some rules - the main being the change from 75 cl to 70 cl in 1991 - each nation retains sovereignty.

Italy is therefore known for tax strips that change every 5-10 years, France for the symbols linked to various taxes created over time, such as the “D”, followed by the CSS tax represented by an “8” in a circle, or, more recently, the logo featuring a pregnant woman. Up until the late 1970s, the UK used the units Proof (alcohol content) and Fl. Oz (volume), before switching to “ABV” and “Vol.” in the 1980s. The list is long, but knowing how to read and understand a label is particularly useful for dating a bottle.

Where to start?

The internet is a great place to start any investigation. First, compare the information available on online auction sites for your product category with sites dedicated to tasting notes and information.

Then, if possible, delve into specialist magazines and books. The most dedicated collectors will have their own library of works whose contents are now often obsolete but whose photos of bottles and labels can attest to the existence of a bottle and be used to date it.

For example : Laphroaig 10 Year Old Islay Malt Scotch Whisky, Importer, Distributor Maison Guerbe SA - La Guide Familier du Whisky, Les Editions de la Boétie (1978 and 1980). This bottling for the French market is particularly rare. Thanks to this book, its authenticity can be confirmed. The bottle is a contemporary of those imported by the Italian company Bonfanti. The distillation period must date from the second half of the 1960s.

Over the years and following visits to distilleries and shows, some people have amassed brochures, catalogues, price lists, newsletters and advertising materials that can also be used to prove or disprove an item’s origins.

Depending on their connections to the whisky industry, others will even be able to make a call or send an email to a contact at a distillery, bottler or distributor.

A list of the most vulnerable distilleries/independent bottlers

Below is a list of the distilleries and independent bottlers most at risk due to the high prices fetched by their bottles. For Japan, the list has grown rapidly. NB.

SCOTLAND

- Ardbeg

Bowmore

Brora

Clynelish

Highland Park

Lagavulin

Laphroaig

Macallan

Port Ellen

Rosebank

Springbank

JAPAN

- Hanyu

Karuizawa

Yamazaki

Yoichi

INDEPENDENT BOTTLERS

- Samaroli (Italian for whiskies)

Cadenhead

Dumpy bottles Brown Labels

Berry Bros ; & Rudd

All Malt – Yellow Label

Gordon & MacPhail

Macallan bottled by G&M

Moon Import (Italian for whiskies)

Sestante (Italian for whiskies)

Velier (Italien for rums)

Caroni, Hampden & autre Demerara