Introduction

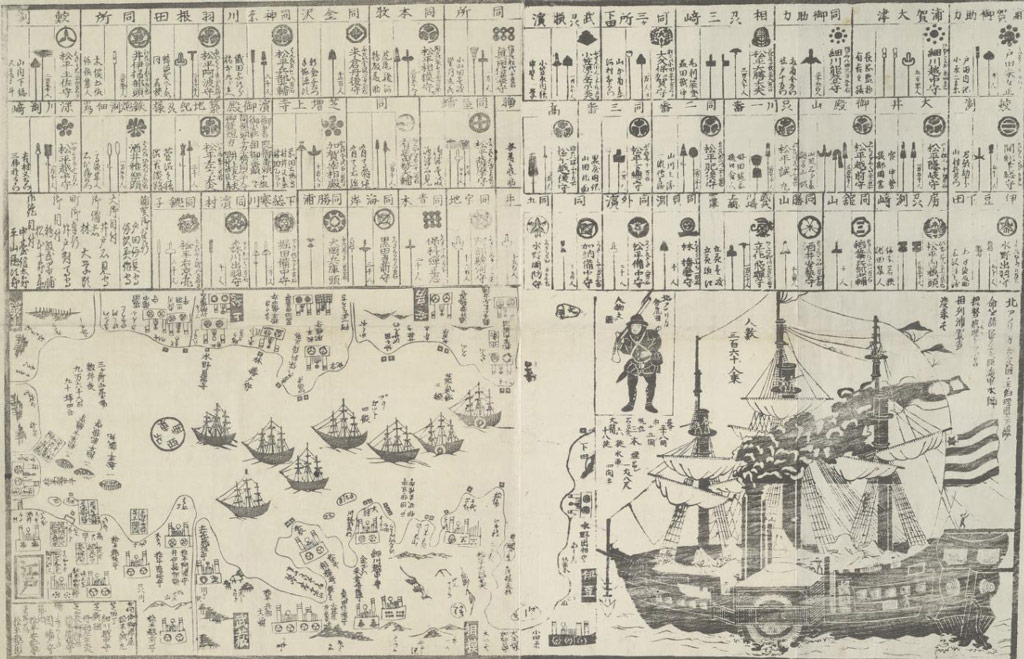

The history of whisky in Japan began under the Tokugawa shogunate on 8 July 1853 with the arrival in the Edo Bay of four warships, the largest of the time, known to the Japanese as the Black Ships due to the thick smoke that surrounded them. At their helm, the commodore Matthew C. Perry carried a letter from the American President Milliard Fillmore requesting the opening of diplomatic and commercial relations between the two countries, with Japan at the time closed off from the rest of the world. As a sign of good will, he brought gifts for the local authorities, including whisky. He returned in February of the next year with a fleet of seven ships with 1,700 men aboard and was granted permission to dock in Kanagawa, near Yokohama. Again, on 13 May 1854, he brought many gifts with him, including a cask of whisky for the Emperor and several cases for Japanese officials. The Convention of Kanagawa, a treaty of friendship between Japan and the United States, was signed under threat of force on 31 May 1854. This unequal treaty, which was quickly followed by commercial agreements and copied by Europe’s major powers, brought a forced end to over two centuries of national seclusion (sakoku).

Japanese representation of the Black Ships

Whisky was at the time a simple curiosity, despite the fact that the start of the Meiji era in 1868 had seen the first attempts to produce yoshu, ersatzes of Western alcohols, amidst growing interest in the West’s scientific and technological modernity - epitomized in Fukuzawa Yukichi’s best-selling work A Call for Learning, published between 1872 and 1876. For all practical purposes, these were spirits that - with varying degrees of success - imitated the taste of alcohols available to the Japanese with the help of infusions and sugar. As Japan gradually regained control of its ports, a weighty tax on imports encouraged the Japanese to produce their own alcohols. Two companies dominated the market, Denbei Kamiya and Settsu Shuzo in the Kansai region. The first contented itself with producing ersatzes, while the second launched a plan to produce a genuine whisky. The project was doomed to failure, but two men later picked up the torch, Shinjiro Torii and Masataka Taketsuru.

Shinjiro Torii (1879-1962): Suntory

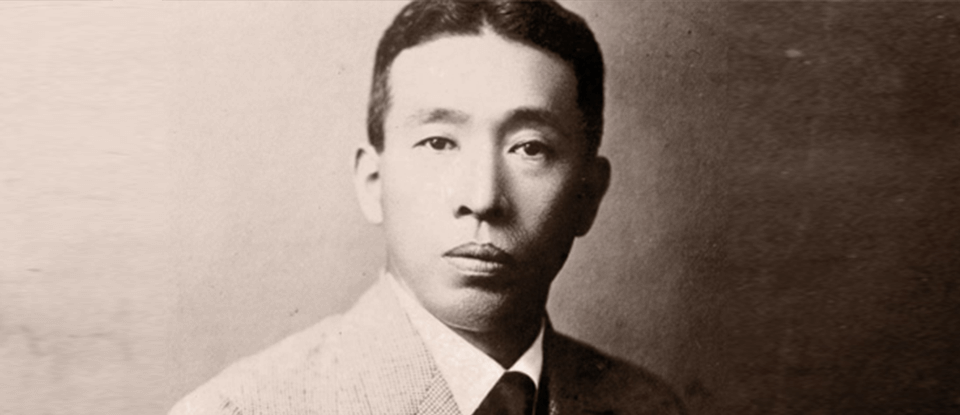

Shinjiro Toii was born in Osaka in 1879. He studied at the Osaka business school for two years before beginning an apprenticeship in the pharmaceutical store Konishi Gisuke, which also sold wine, brandy and whisky. The blends were essential to the pharmacy and it was here that Torii learnt the basics of chemistry. After later working for a short time with a painter and dye seller, he then set up his own business, Torii Shoten, which he opened in the Nishi district.

In the store’s early days, he primarily sold wine and tinned food but soon developed an interest in Western alcohols. After tasting a port from a Kobe broker of Spanish wines whom had met whilst working at Konishi Gisuke, he decided to specialize in wine and renamed his store Kotobukiya Liquor Shop. His products were poorly received by the local Japanese, who found the wines too acidic or too bitter and preferred their own flavoured versions. Deciding to put his blending skills to use, he then began mixing his wines, adding flavourings and sugar. Although he was able to clear his stock with his first creation in 1906, it was only in 1907 that he really hit gold with his Akadama Port Wine. In 1911, he launched his own whisky ersatz, Hermes Old Scotch Whisky, but his real aim was to produce a whisky according to the state of the art, like the products produced in Scotland.

Shinjiro Torii, the founder of Suntory

Encouraged by sales of his Akadama Port Wine, he began searching for a Scotsman who could teach him how to make whisky. Shortly, however, an acquaintance named Dr. Moore told him of a young man who had travelled to Scotland in 1918 to learn about whisky - a certain Masataka Taketsuru. In June 1923, Taketsuru began working for Shinjuro Torii as the manager of the future distillery. The two men could not agree on where the distillery should be built. Taketsuru preferred Hokkaido, but Torii was more interested in practical considerations, such as transport and proximity with the head office. Eventually Torii decided his way was best and the distillery was built in Yamazaki and placed under Taketsuru’s control.

The Yamazaki distillery, halfway between Osaka and Kyoto

Construction of the distillery began in 1923 and was completed the following year. The first drop of spirit left the still on 11 November 1924, a little after midday, but the result left a lot to be desired and, at the end of the season, Taketsuru returned to Scotland to learn more. Progress was slow to arrive and money soon began to run out. To keep finances afloat, Torii began developing a range of other products, including pepper, soy sauce, syrup, curry and tea. And then, finally, in April 1929, Suntory Whisky Shirofuda was released (Suntory: a contraction of the red sun of Akadama and the Japanese flag, and Torii; Shirofuda: white label). It was a flop, with Japanese consumers turning their noses up at the smoky taste. It would not be until 1937 that Torii finally found the recipe for success with Kakubin, which literally means “square bottle”.

Masataka Taketsuru (1894-1979): Nikka

Masataka Taketsuru was born in 1894. The third son of Keijiro Taketsuru, the director of a saké brewery in Takehara, near Hiroshima, he studied chemistry at Osaka high school and signed up for a new class on fermentation. During his studies, he developed a growing interest in Western alcohols. In 1917, Taketsuru was introduced by his former school friend Kiichiro Iwai to Kihei Abe, the owner of Settsu Shuzo. At the time, Settsu Shuzo was the main producer of industrial alcohol and yoshu in the Kansai region. Taketsuru explained his plan to travel abroad to study distillation and Abe was instantly impressed. He recruited the young man to Settsu Shuzo in May 1917, much to the disappointment of Taketsuru’s father, who wanted his son to continue his studies and take over the family business.

Initially joining Settsu Shuzo as a chemist, he quickly rose to Head of Production for Western alcohols. At the time, imports of authentic whisky were on the rise and local producers began to fear for the commercial future of their ersatzes. Creating a “real” whisky became a necessity and Kihei Abe decided to send one of his employees to Scotland, entrusting the delicate task to the young Taketsuru. Although his parents were against the move, still hoping that their son would take over the family brewery, Abe convinced them to allow him to leave and they the brewery was eventually passed on to close relations.

In July 1918, Taketsuru left for Scotland on board the S.S. Tenyo Maru, making a stop in San Francisco. He arrived in the United Kingdom on 2 December 1918. He then enrolled in chemistry classes at Glasgow University and the Royal Technical College, where he met Isabella (Ella) Lilian Cowan, who was studying medicine at Glasgow University. She introduced him to her family in Kirkintilloch, a small village in north-east Glasgow, where he moved in early 1919.

In April, he went to Elgin, to the heart of Speyside, to learn under J.A. Nattleton, author of The Manufacture of Spirit (1893), the leading book on distillation at the time. The professor agree to take him on, but his fees were far too high for the young Taketsuru, who decided instead to contact the distilleries in the region. Moved by his interest, Longmorn’s manager J.R. Grant agreed to take him on as an apprentice free-of-charge for a few days. There he learnt everything there was to know about producing and maturing whisky.

Also keen to learn how to produce grain whisky, Taketsuru then went to the Bo’ness distillery, where he worked as a replacement for two weeks at the start of the summer of 1919. He so enjoyed working with the distillery’s Coffey still that he asked to stay on a week longer to learn more about fermentation. In the autumn, he visited the vineyards of Bordeaux and, when winter came, married Jesse Roberta Cowan, Ella’s older sister, also known as Rita. He proposed at Christmas and they married on 8 January 1920, against the wishes of both their families. Mrs Cowan tried to have the marriage annulled and Taketsuru’s parents sent Kihei Abe to sort things out. Abe was less than enthusiastic, as he was hoping Taketsuru would marry his own daughter and remedy his lack of male heir to take over his business.

Masataka Taketsuru, the founder of Nikka, and his wife Rita

Although Taketsuru was prepared to stay in Scotland for Rita, she knew his dream was to produce whisky in Japan and agreed to follow him there. First, however, he moved to Campbeltown, where, with the help of Professor Forsyth James Wilson, Taketsuru’s supervisor at the Royal Technical College, he began an apprenticeship at the Hazelburn distillery, spending five months filling the pages of his notebook entitled “Report of Apprenticeship: Pot Still Whisky”. This was the notebook that would form the basis of whisky production in Japan.

He returned to his home country with Rita in November, determined to make the most of what he had learnt in Scotland, but the economic climate was difficult and Settsu Shuzo was struggling, forcing the business to abandon his project. Taketsuru was promoted to head engineer, responsible for overseeing the production of whisky ersatzes, much to his disappointment. His initial aspirations unfulfilled, he resigned in 1922. A friend of Rita’s then helped him find work in a school, where he taught applied chemistry, before being recruited by Shinjiro Torii. Following their first failures, the relationship between the two men eventually turned sour and Taketsuru was sidelined to a brewery the group had bought in 1929. He resigned at the end of his contract in March 1934.

Yoichi distillery, Hokkaido

Three months later, on 2 July, he founded his own business with the help of various investors, including some met through Rita, who taught their children English. This company would become Dai Nippon Kaju Co. Ltd. (the Great Japanese Fruit Juice Company), a name shortened to Nikka in 1952. Noting its similarities with Scotland, Taketsuru remained convinced that Hokkaido was the best place to set up a whisky distillery and soon found the perfect location near the Yoichi river, one mile from sea and surrounded by mountains. The distillery was up and running by October.

At the start, Taketsuru produced an apple juice and cider to bring money in so he could begin producing whisky, a task that would be expensive and take more time. His first apple juice was sold in 1935 but later returned because consumers disliked its cloudy appearance. He decided turn it into apple brandy. Increased finances enabled him to buy his first still, created by Watanabe Copper & Ironworks in Osaka, who also produced Yamazaki’s stills and based the design the stills at Longmorn, where Taketsuru had studied in Scotland. He was granted a distillation licence on 26 August 1936 and immediately set to work, using his still for both the first and second distillation. In 1940, Dai Nippon Kaju released its first products, Rare Old Nikka Whisky and Nikka Brandy.

Conclusion

It would be impossible to provide every detail of the century that followed. What we can say, however, is that Japanese whisky was generally synonymous with blended whisky until the first Japanese single malt was released by Suntory in 1984 - although Karuizawa had technically released its own malt in smaller quantities in 1976. Quality at the time varied depending on how much malt was used in the blend and the alcohol content. In the mid-1980s, interest began to wane and the industry remained in crisis for many years until the recent radical change in situation both in Japan and abroad.

For a long time limited to its domestic market, Japanese whisky gradually spread to the rest of the world in the 2000s. That was when a handful of companies began importing Suntory and Nikka’s whiskies to Europe. These were well-priced and delighted enthusiasts curious to discover whiskies from a country whose history with the spirit was generally not known about. Regular awards at competitions, as well as articles in trade and general magazines and word of mouth all led Japan to find its place among the world’s greatest whisky-producing countries and in the 2010s demand even rose so high that the country’s leading distilleries were forced to make radical changes to their ranges due to a lack of stock.

Karuizawa distillery, closed in 2000

The popularity of Japanese whisky extends to closed distilleries like Karuizawa, Hanyu and Kawasaki, victims of a lack of both local and global interest in whisky in the mid-1980s. Few casks were kept following their closure and bottlings released in the late 2000s now fetch jaw-dropping prices due to their rarity and quality. The same phenomenon is seen with old limited editions and discontinued bottlings of Suntory and Nikka. This success has inspired new vocations and Ichiro Akuto became something of a pioneer when he founded the Chichibu distillery in 2008, in a time when such a move was still far from simple. Other examples of ambitious distilleries emerging in recent years include Akkeshi and Shizuoka, and, in a market where demand for premium Japanese whisky is still largely unmet, the success of these new players seems almost guaranteed.

Ichiro Akuto, founder of the Chichibu distillery

For anyone who would like to learn more about Japanese whisky, we highly recommend Stefan Van Eycken’s excellent book Whisky Rising, to which this article is largely indebted; The Definitive Guide to the Finest Whiskies and Distillers of Japan (Cider Mill Press Book Publishers, 2017) and Dave Broom’s travel book The Way of Whisky; and A Journey around Japanese Whisky (Mitchell Beazley, 2017); For a more general overview of Japan’s history, we consulted Pierre-François Souyri’s Nouvelle Histoire du Japon (Perrin, 2010) and Francine Hérail’s L’Histoire du Japon des Origines à Nos Jours (Hermann, 2009).